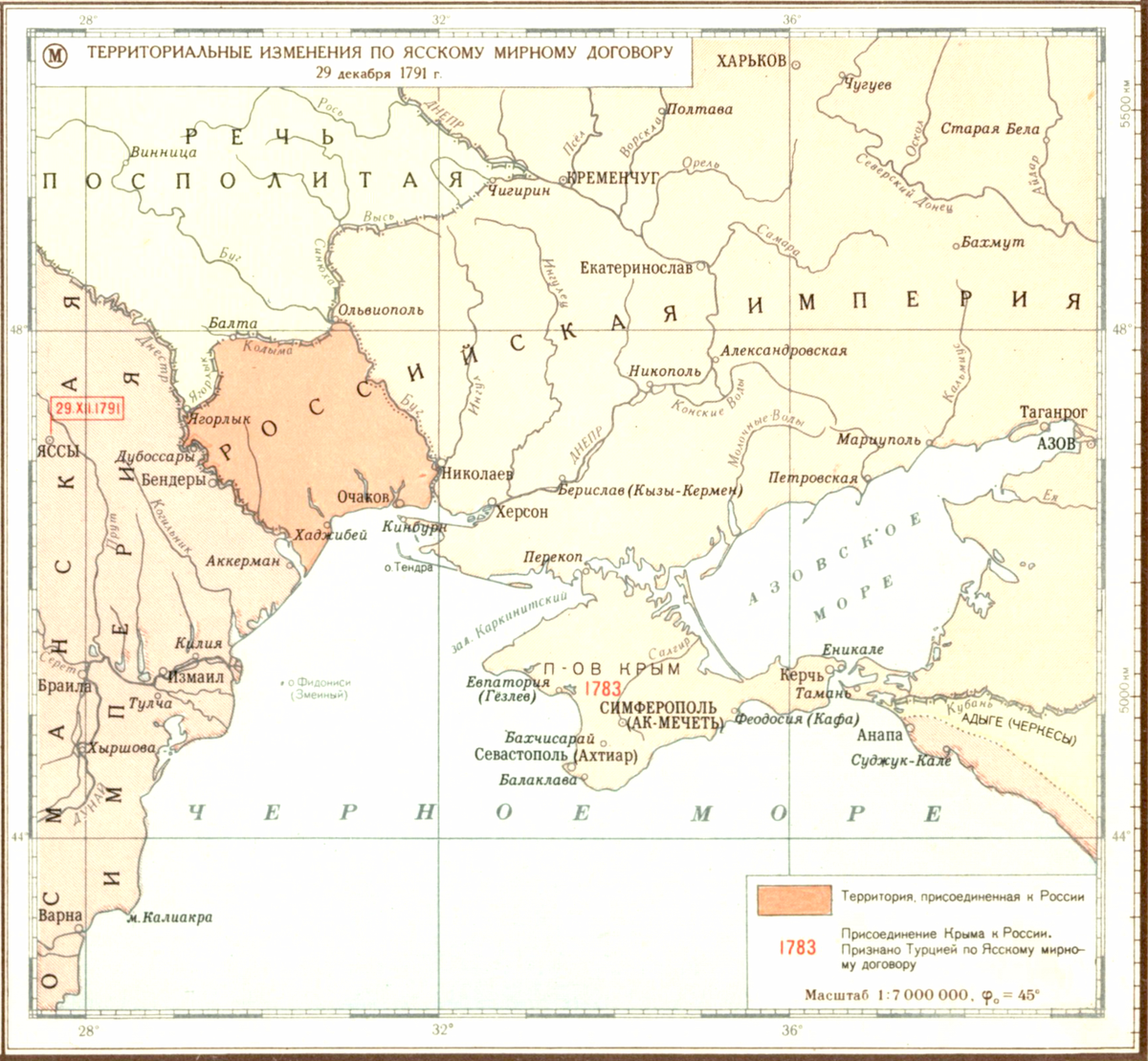

228 years ago, on January 9, 1792 (December 29, 1791 in the Julian calendar), there was Treaty of Jassy signed, which ended the Russo-Turkish war of 1787-1791. One of its conditions was the inclusion of land between the Southern Bug and the Dniester in the Russian Empire.

In this publication, we will not talk about the hostilities during which there was the military genius of Suvorov and Ushakov. You can read about the Russian-Turkish war of 1787-1791 here and here.

We will only touch upon the consequences of this treaty, which is truly groundbreaking for our region.

By the way, the Ottoman Empire started the war, pushed by Britain and France. They decided to be proactive. The fact is that the so-called Greek project of Catherine II made a lot of noise in Europe. It assumed the division of the European part of the Ottoman Empire between the Holy Roman Empire, Russia and the Venetian Republic and the creation of two independent states: the new Byzantium and Great Dacia. The entire Black Sea and Aegean coast of modern Turkey, including the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles straits, as well as Greece and Bulgaria were to be included in the first. The second was to unite the Moldavian and Wallachian principalities. According to the Greek project, the lands between the Dniester and the Southern Bug were to become part of Russia.

The Greek project was not fully realized because of an unexpected exit from the war by the Austrians on the side of Russia. Ant the fact that in St. Petersburg they did not forget about the Greeks is evidenced by the names of the newly formed cities in the Novorossiysk Territory: Odessa, Tiraspol, Grigoriopol, Ovidiopol, Olviopol. Toponymy was supposed to prompt the Balkan peoples: "Your liberation from Turkish rule is not far off, but for now Russia is ready to shelter you on newly acquired lands."

It cannot be said that the Dniester-Bug Mesopotamia was completely deserted, but still its massive settlement began precisely after the signing of the Treaty of Jassy. Some articles of this treaty contributed to this. According to them, Russia was proclaimed the defender of Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire and the Danish principalities vassal to it. And Turkey did not have the right to prevent the relocation of its subjects to the Russian Empire.

"Melting pot of nationalities": such was Catherine II`s vision of this region future. In part, these plans of the Empress came true. Even today in Pridnestrovie, unlike many other places, all peoples have preserved their culture and language. A book “Colonization of the Novorossiysk Territory and its First Steps on the Way to Culture” by D. I. Bagaley was published in Kiev, in 1889. The author of this work describes the first Novorossiysk settlers as follows: “The composition of the population was very diverse: Greeks, Serbs, Bulgarians, Moldovans and Volokhs, Malorossians-Zaporozhets, Hetmans, Great Russians-Old Believers and Orthodox, immigrants from Poland and fugitives from central Russia, soldiers and so on. Representatives of various nationalities lived in the same village." Since then, by the way, nothing has changed. The book says a lot about how those lands had been settled by Russians (according to Bagaley, Russian people) and Ukrainians (Malorossians).

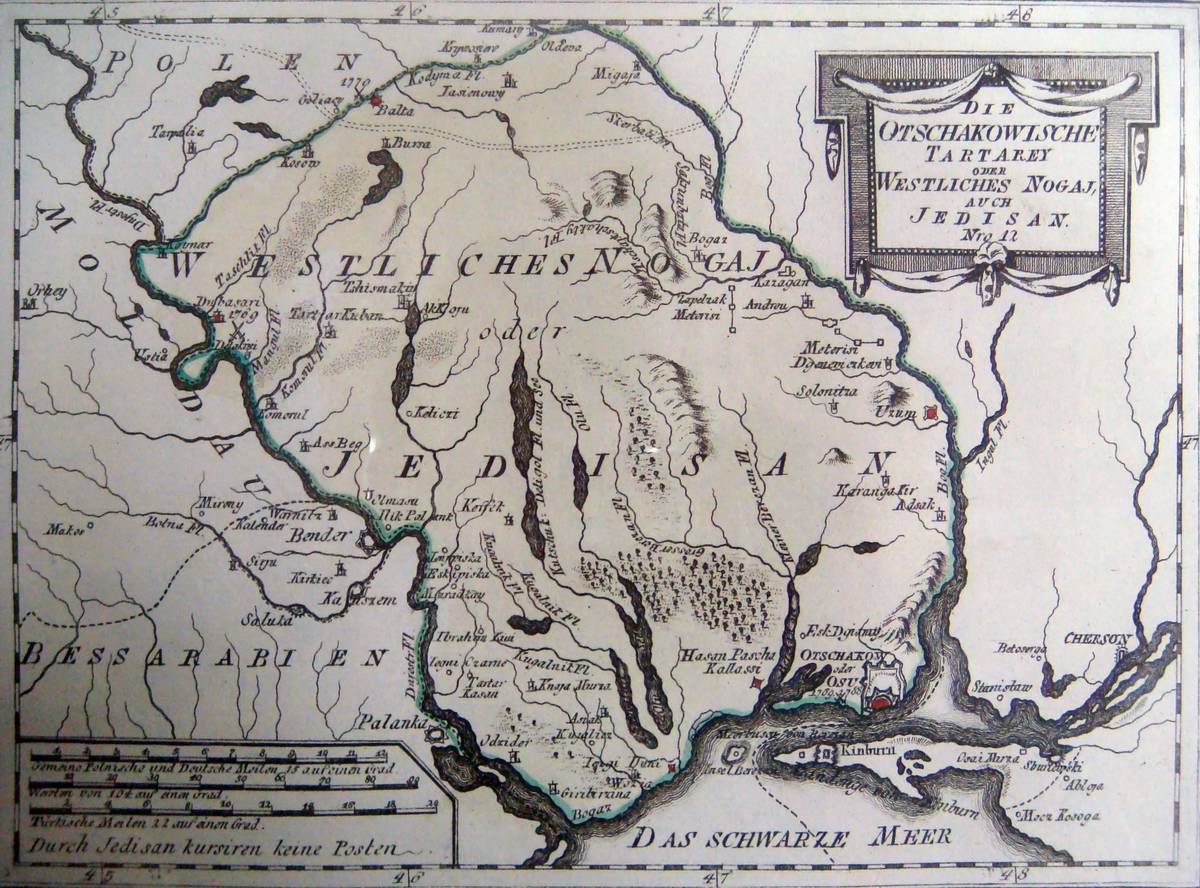

Edisan Region. Wild West of the Russian Empire. Austrian Map of 1790.

In his book, speaking of the “foreign nations” who settled here, Bagaley makes a small reservation that he has included Moldavians in that category. In that time, Bessarabia was not yet a part of Russia, and the principality of Moldova that had existed in the Ottoman Empire had been a foreign state. Small waves of Moldavian immigrants were noted in both Peter's and Elizabethan times. “At the end of the 18th century, another party of Moldavians settled cities and villages along the Dniester to Ovidiopol, New Dubossary, Tiraspol and others. At that time, 26 people of Moldavian boyars and officials received up to 260,000 acres of land in Tiraspol and Ananyevsk counties, and founded 20 villages and several khutors. Each of them received several thousand tithes (from 4 to 24 thousand),” Bagaley writes. But some representatives of the Moldovan nobility decided to abuse their refugee status a little.

“Abusing the Russian government good grace, one of the Moldovan boyars, Strudza, expressed too excessive demands. He asked for 9 villages for himself, where there were 11,000 male souls who lived there and 46,000 acres of land. Strudza found support from the famous secretary of Knyaz Potemkin Popov, but he was opposed by the Governor Kakhovsky, and it was a great honor for him. The Russian government had to protect the uninvited Moldovan immigrants from possible enslavement in a new place by their own countrymen under the ranks and titles. Therefore, the “Regulation on Mandatory Villagers” specifically for Moldovans was published. “They ( Moldavian peasants) were recognized personally free. The landowner could only dispose of the land on which he lived and which was his property. According to Moldavian custom, they were obliged to pay tithing for this land from agricultural products and cattle breeding, did forced labor for 12 days a year, and render assistance in some other cases (for example, harvesting vineyards).”

Model of Tiraspol Fortress

The Novorossiysk Territory was populated not only by Orthodox Christians. There were a lot of people eager to settle here from numerous German states, France, Switzerland, and other European countries. They were literally lured with all sorts of benefits. Again, we quote D. I. Bagaley: “The most important benefits provided to the new settlers were the following: they could receive travel expenses from Russian residents abroad and then settle in Russia, cities or in separate colonies. They were granted freedom of religion, were exempted for a certain number of years from all taxes and duties (settled in colonies for 30 years). They were given free apartments for half a year; an interest-free loan was issued with repayment in 10 years for 3 years. Settled colonies were given their own jurisdiction. Everyone could import duty-free property and 300 rubles of goods with them. If someone started a factory that had not previously been in Russia, then he could sell duty-free goods produced by him for 10 years. In addition, duty-free fairs and tenders could be instituted in the colonies. ”

Bagaley accords an important place in the development of new lands to the Greeks and Bulgarians who fled to Russia from the Ottoman Empire. With a few exceptions, originally Greek settlers settled in the newly formed cities, giving a strong impetus to the development of trade and the beginnings of industry there. Besides the Greeks, among those who quickly settled in Novorossiya were also Arnauts (Albanians) and Jews. The main occupations were the same as the Greeks had. Both the first and the second also had a penchant for agriculture, but, unlike the Greeks, they did not form separate rural settlements of their own. In his book, Bagaley highlights the Bulgarian colonization of the region: “One party of them (Bulgarians) settled near Olviopol (the current city of Pervomaisk, Nikolaev region) on the Sinyukha River, while others headed to new cities: Tiraspol, New Dubossary, Grigoriopol and Odessa at the beginning of the XIX century. In 1821 there were 5,863 people of both sexes in the Kherson province ... Bulgarian colonies had an important influence on the development of local agricultural culture.”

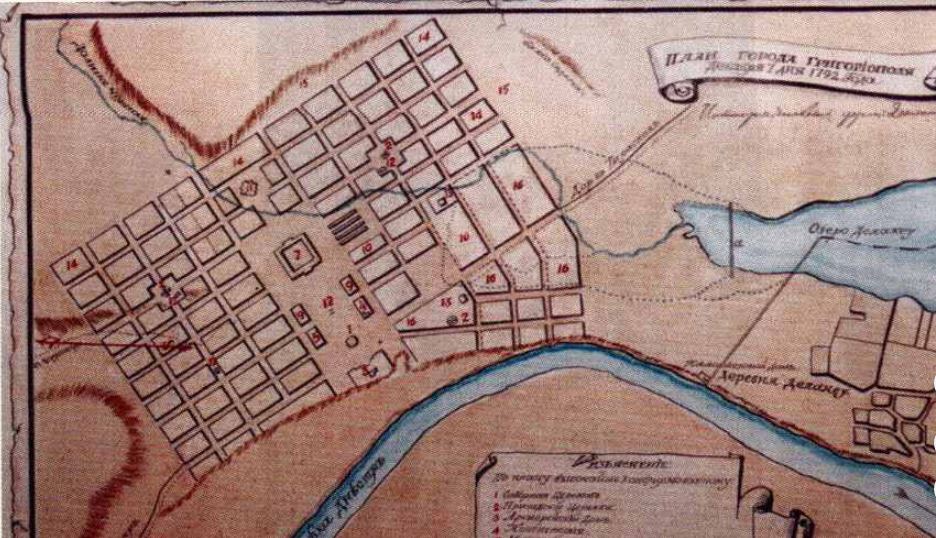

City Plan of Grigoriopol

Bagaley also includes Poles as the foreign Slavs who moved to the Novorossiysk Territory. Simpler people were immediately included in the Bug Cossack and Hussar regiments, which were formed in the Catherine era from immigrants: Serbs, Moldavians, Bulgarians, Georgians and other nationalities from the Russian borderland. Subsequently, the Poles from among the former Bug Cossacks and Hussars, along with the Lithuanians and Tatars, became the basis for the formation of the first Russian Ulan Regiments. Others went for business purposes to the cities.

“Finally, the Polish magnates, having received large land plots from the Russian government in Novorossia, transferred peasants from Poland there; but generally speaking, the number of Polish immigrants was small,” Bagaley writes.

The Armenians had a particular status. There was a city called Grigoriopol specially designed for them, which for Armenians from all over the world became a kind of symbolic one.

“A part of the Armenians left the Dniester and founded the city of Grigoriopol. Armenians who left Izmail, Bendery, and other cities asked for many benefits for themselves. Kakhovsky (Governor) considered it possible to satisfy their request. The Empress cared about the fate of these Armenians. She wrote to Governor Kakhovsky that “not only all who crossed our borders be preserved, but also their one-countrymen, seeing them as prosperous, join them.”

That was how our land imagined. The land where all people would prosper, regardless of their nationality.

Anton Egorov