This week, residents of Grigoriopol celebrated 226 years since their hometown founding. In the scientific reference book devoted to the twentieth anniversary of the PMR State Archive, it is said that the Armenian colony city of Grigoriopolis was started to be built on July 25, 1792 on the place of the Chernaya outskirts.

Its name is associated with the memory of two historical figures: Gregory was the founder of the Gregorian religion of the Armenians, and Prince Grigory Potyomkin-Tavrichesky, who took an active part in the founding of the city. The settlement was created by the Russian authorities specifically for the Armenians, who moved to Dubossary from the territory of the Ottoman Empire during the Russian-Turkish war of 1787-1791. In Grigoriopol, the plates of the old Armenian cemetery still survive to this day. At the same time, there are interesting facts that testify that the history of the city of two Grigories began long before its appearance.

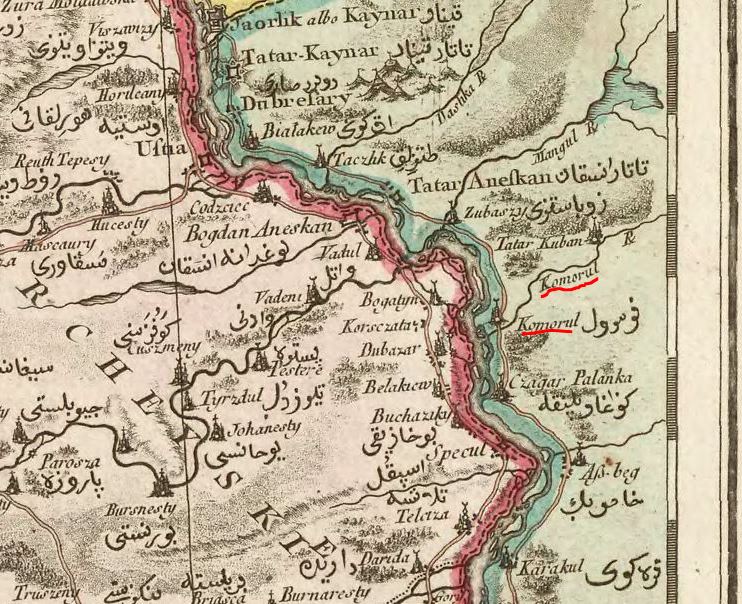

On the old maps of the XVIII century, southern Pridnestrovie appears to us as a completely different world. Contemporaries called it the “Wild Field” and the “Tatar Desert”, implying that this territory is not inhabited at all, and there is nothing on its spaces except the Ochakov Tatars nomads and dense steppe vegetation. But the maps possessed by travelers of that time contain many unusual names for us, however, geographically connected with present cities and villages. Among them, the mysterious Komorul is an unknown settlement at the mouth of the river of the same name, noted by many geographers, which is already a rather interesting fact. And although this topic is still waiting for its researchers, some representatives of the local history cohort have already connected Komorul with the village of Dorotskoe, Dubossary district. However, careful study of old maps leads to the idea that such a conclusion was premature.

On the detailed map of Poland in 1772 by the Italian geographer Giovanni Rizzi Zannoni, there are many settlements indicated in the territory of Pridnestrovie along the Dniester. To the south of the Yagorlyk River there is only one name familiar to us - Dubresary. All the others are exotic, supplied to the same Arabic version of the toponym.

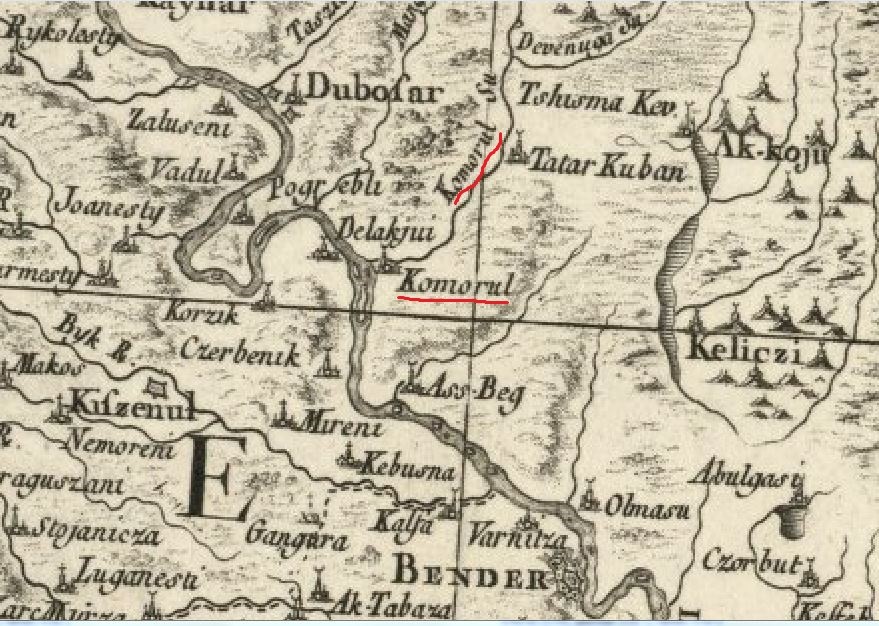

Tatar-Kaynar and Tatar-Anefkan fortresses in the vicinity of the current Dubossary are remarkable. Downstream are Karakul, As-beg, Czagar-Palanca and Komorul. The last toponym is the river that flows into the Dniester, and to the north of it, the Mangul riverbed is traced. Today, there are only picturesque valleys and drying streams that have survived from those rivers. However, contemporary Black Creek in Grigoriopol and Tamashlyk (Mary valley) in the Dubossary region are recognized in them.

On another map of Zannoni (the Ottoman Empire in 1774), the Dniester is more detailed: the winding at Dubossary is drawn more precisely, with all the bends. Here the settlement of Komorul is located south of the “Koshnitsa Peninsula”, presumably on the place of the modern Grigoriopol.

Similar topographic reference is also visible on the map of Moldova and Bessarabia Bartolomeo Borghi of 1789:

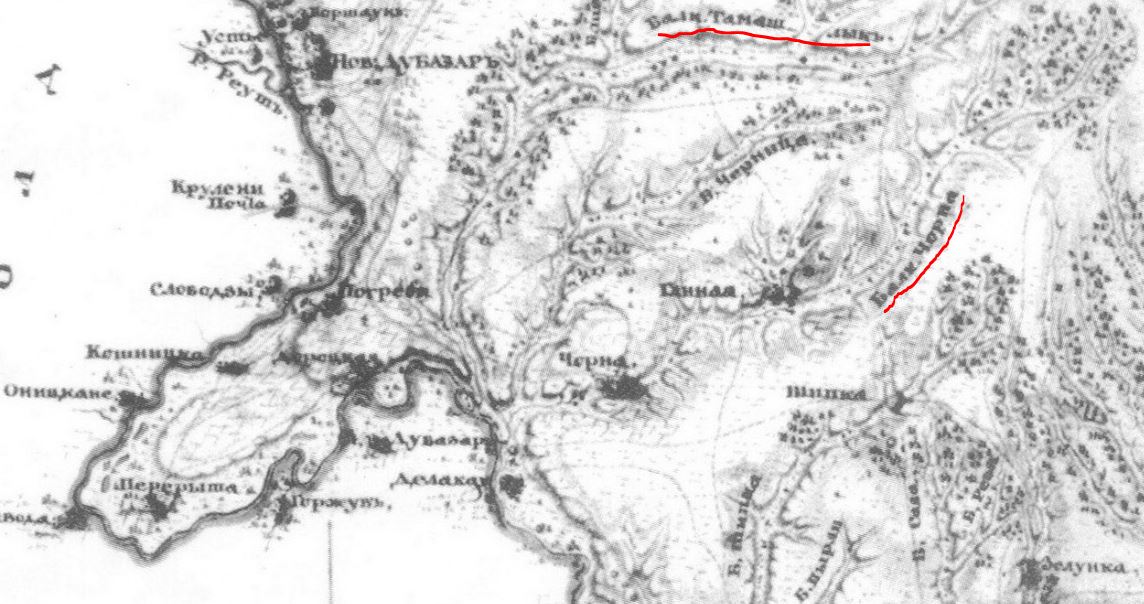

And on the Austrian map of the Edissan horde of 1790:

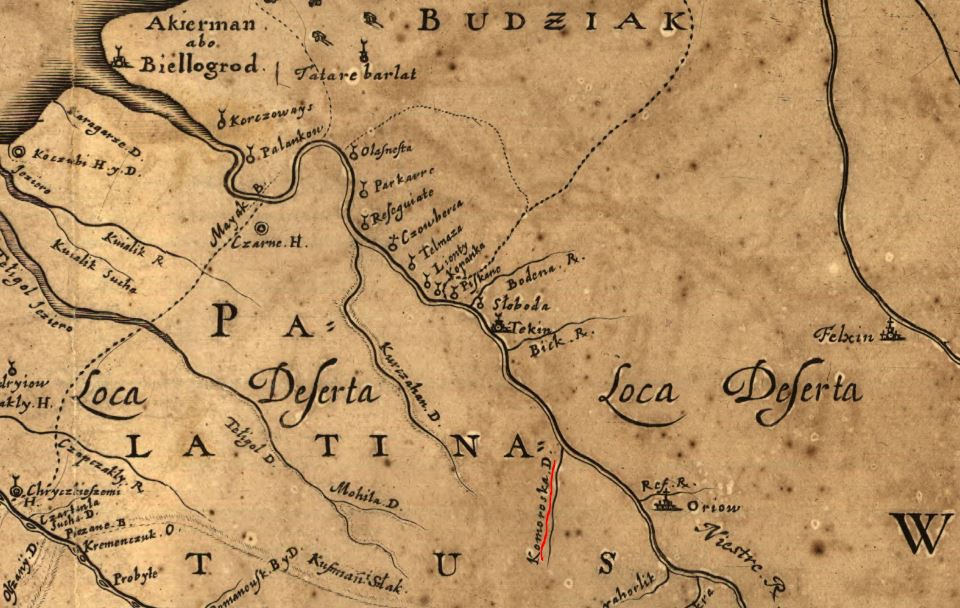

There are, however, earlier sources mentioning Komorul. On the “General Plan of the Wild Fields, easier referred to as Ukraine, with the adjacent provinces” of 1648 by the Dutch engraver and cartographer Wilhelm Gondius between Tekine (Bendery) and Yagorlik, the left tributary of the Dniester - Komoraska is marked.

A detailed description of these places is also contained in the “Geographical map depicting the Ozu or Edisan region, attached to the Russian state” of 1791. It was painted at the time of Yassy peace signing, according to which the southern territories of Pridnestrovie were part of Russia. There are no longer visible names marked on European maps, but a simple comparison allows us to relate the above-mentioned Komorul and Mangul respectively to Chorna Beam and Tamashlyk Beam.

Interestingly, there is no Grigoriopol on this map, but a small settlement of Chorna is noted. Now let's try to summarize the data. The city of Grigoriopol appears on July 25, 1792 on the place of the Chernaya outskirts, in the valley of the river of the same name. Its course is marked on the European maps of the 70-80s of the XVIII century under the name Komorul. The same is called a certain settlement at its mouth, at the place where Grigoriopol then spread out. It turns out that Armenian colonists settled in the places that had already been inhabited. And chronologically, the two settlements are not so far from one another: Komorul is on the Italian maps of 1772 and 1774, as well as on the Austrian map of 1790. However, on the Russian map of 1791, the toponym Komorul is no longer there, but in this area there is Chernaya outskirts. If the designated logical chain is correct, then the following questions arise: is there a connection between Komorul and Chernaya, who were their inhabitants and why this topic has not received a detailed consecration in the national historical science?

We have not figured out the origin of the word Komorul and its meaning. It is phonetically similar to Turkism, but similar words are found in Moldavian and Russian languages. Moreover, in Moldavian language there are several different meanings: komoarae - “treasure” and a comor – “a breed of sheep”. In Russian language “komora” means cage, closet and pantry. An interesting combination of meanings: the treasure and the crate-closet-pantry – there are something hidden, underground.

Coincidence or speculation, but the residents of Grigoriopol still tell stories about mysterious underground structures. Nobody knows who and when built them, but old-timers say that, most likely, they appeared “at the time of the Turks and Tatars”, that is, before Pridnestrovie became part of Russia. It is said that under the city there is a whole maze, the tunnels of which were eventually walled up and adapted by local masters to ordinary cellars. From time to time during the construction of buildings or communications laying they find catacombs lined with stone in Grigoriopol. An ancient dungeon entrance was recently discovered in a household adjacent to the main street of Grigoriopol.

The head of the documentation and archives department of the Grigoriopol district, Svetlana Kazakova, says that, as a schoolgirl, she and her peers investigated the tunnel, which went under the Dniester river.

“We did not get to its end, although we`d been walking for about half an hour. They turned back because they were afraid to go further” – Kazakova recalls, noting that the tunnel height was about 1.8 m, and its arch was lined with stone.

According to her, there are a lot of such tunnels under the town. Over time, some of them were walled up by residents because of fear of the unknown, others were engulfed during the construction of government buildings and shops.

Natalya Berzan, head of the local branch of the Pridnestrovian Geographic Society, reported that during construction works in the center of Grigoriopol (in the 70s of the last century), people came across a two-level underground structure. This space, however, was covered with sand, as recall eyewitnesses.

“The underground structures chain seems to have two levels. There was a time when during a rain one of the basements turned out to be filled to the top. But the water was gone down very quickly, and through the gap in the floor one could see the lower tunnel” - Berzan said.

“Grigoriopol undergrounds” became another story in oral narratives about Pridnestrovian labyrinths, which were also found in Dubossary, Bendery and, according to indirect data, even in Tiraspol. To discover the secret of their origin and understand what they were built for, specialists need to undertake a great deal of research expeditions. So far, with all certainty, we can only say that in the history of our region there are a lot of white spots.

Alexander Koretsky