A tomb of a Scythian warrior of the 4th century BC, discovered by Pridnestrovian archaeologists this spring, gave them an interesting surprise. First, they found a quivered set of bronze arrowheads (about thirty pieces), a Thracian clay bowl, burned ritual stones and a limestone slab for preparing dyes. They also found the bones of sacrificial food and corroded iron fragments that archaeologists took for a knife blade, destroyed by time and moisture. Meanwhile, the main discovery awaited them in the lab. The senior fellow of the research lab "Archeology", Vitaly Sinika, has shared the story of this incredible discovery with Novosti Pridnestrovie.

In April, archaeologists from Pridnestrovian State University began the rescue excavation of 13 mounds a few kilometers away from the village of Glinoye, Slobodzeya District.

First, they examined the remains of the embankment of a small earth pyramid of the Bronze Age belonging to the second half of the 4th - first half of the 3rd millennium BC. The researchers made certain it had been constructed in ancient times as soon as they reached the core of the mound - the central tomb. However, they were late - the tomb had been completely robbed as early as the first millennium BC. And it had not been so easy for tomb raiders to get to it as back then the mound had not yet been ploughed up, and they had had to shovel the considerable amount of tamped earth. Judging by the traces of the grabbed, they knew exactly where the chamber was. But most importantly, the robbers did not notice another tomb, which had appeared in the mound at least two millennia (!) before the construction of the steppe pyramid.

This tomb was built for a Scythian warrior in the 4th century BC, judging by the artifacts found in it. The artifacts, the archaeologists believe, have a ritual significance and are somehow connected with the ideological beliefs of the Scythians. It is difficult to say today what exactly they symbolise as apart from some references to the Scythians in the writings of ancient authors, there is no additional written evidence of this culture. So only archaeology allows us so far to collect bits of information about this interesting and mysterious nomadic civilization of the Great Steppe of Eurasia. And every discovered artifact is not just an ancient object but a kind of database. These artifacts can tell us a lot about ancient art, knowledge, worldview, symbolism and way of life. Not only things can "speak" but also human bones, whose investigation reveals the food, illnesses and injuries of ancient people.

For example, the limestone slab from the tomb of the Scythian warrior. It shows the traces of ocher - a natural pigment, consisting of iron hydroxide with an admixture of clay. It was used to prepare dyes, and the stove, judging by its dented surface, served as a kind of table for rubbing ocher.

The question arises as to why the slab was placed in a warrior tomb? What does it symbolise in the funeral ritual? Today, scientists can only put forth versions based on a comparative analysis of ancient mythology or search for a simple explanation: the Scythians, allegedly, believed that this object would be useful for the deceased "in the kingdom of shadows." Anyway, the accumulation of data will answer many questions in the course of time.

The archaeologists will try to answer one of them in the near future. The warrior tomb had, as was mentioned above, the corroded fragments of iron. Unlike bronze, this metal corrodes rather quickly. Therefore, the researchers did not expect to "pull out" information from this iron piece.

"Initially, we took it for a knife blade - an ordinary find in Scythian tombs. But when we collected all the iron fragments that had undergone severe corrosion for more than two thousand years, we could hardly believe our eyes," said Vitaly Sinika.

The fragments were collected scrupulously, centimeter by centimeter. Each fragment had been previously cleaned from the smallest foreign elements. This work requires pinpoint accuracy: the restorer uses only a small needle as a tool. All the elements are immersed in pure medical alcohol in order to squeeze out the moisture damaging iron. The fragments are impregnated with a chemical solution on an adhesive basis and under a large magnifying glass are fitted together, just like a jigsaw puzzle. The whole product is thus restored from the hundreds of tiny iron fragments. The process can take days, weeks, sometimes months and even years. In our case, it took us about a month to reconstruct only the largest fragments.

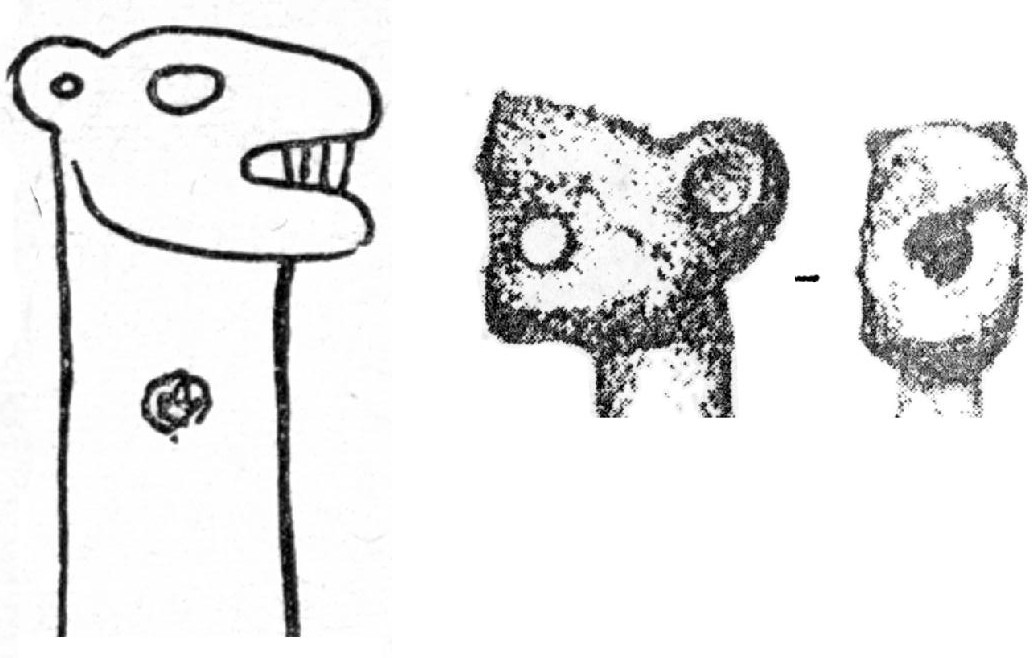

But this was enough to see the profile of a predator, perhaps a wolf. It turned out that this is not the knife blade, as the archaeologists initially assumed, but a handle with a zoomorphic top.

"We assume that this is a flat image of a wolf's head - the ear of an animal, an open mouth and even its eye are clearly discernible," says Vitaly Sinika.

At the moment it's definitely possible to say that this find is unique find the North-Western Black Sea Region. Such old handles have not been found in the region of the lower Danube, in the Budjak steppe, or in the mounds of the Dniester basin.

Anatoliy Kantorovich, the biggest specialist in the Scythian animal style from Moscow State University, says that such handle images are found in the forest-steppe zone and date back to the 6th - 5th centuries BC. Three of them have been discovered in a large Scythian-period archaeological landmark - Bilske Horodyshche (Bilsk Hill Fort) in the Poltava region of Ukraine.

The tops of knife handles from Bilsk Hill Fort:

Meanwhile, the tomb, according to Vitaly Sinika, was not built earlier than in the 4th century BC. According to the archaeologist, this is seen from the specific forms of bronze arrowheads, which are known only from the beginning of the 4th century BC and not before. It turns out that between the similar artifacts of Bilsk Hill Fort and the Scythian tomb near the village of Glinoye there is a time abyss of 150 years (!).

Then how did this knife with the zoomorphic handle get into the tomb of the warrior? Maybe it was passed from hand to hand by the five generations of owners? Or maybe knives with such handles were made at a later time as well? Or is it necessary to revise approaches to the existing timing methods? To understand these issues, the archaeologists will have a lot of research to do anyway.

Still, the "steppe wolf" or any other mysterious predator decorating the handle of the knife will go down in the history of research as a magnificent example of the Scythian "animal style" from the North-Western Black Sea Coast, where such objects are a real rarity. Strong corrosion of metal has changed its original image. One can only imagine, using, of course, its extant counterparts made of more durable materials - bone, horn or bronze, what this zoomorphic knife looked like 2,300 years ago.

Ancient bronze bridle plaque found near the village of Tokmazeya, Pridnestrovie:

Alexander Koretsky